The case for using avatars in today's digital learning is not hard to make.

We are present at the Second Annual Sloan-C International Symposium on Emerging Technology Applications for Online Learning because of the future--the future of digital education and a desire to explore its possibilities. This presentation argues that the avatar learning agent will continue to emerge as a key component in digital learning environments, whether 3D immersive worlds or the world of Adobe Captivate.

The argument begins with some old news: Higher education has been radically transformed by digital technology and the digital generation. Over a decade ago, The Drucker Foundation (Hesselbein, Goldsmith, & Beckhard, 1997) warned that our traditional teaching methods were outmoded and the physical institutions themselves were "hopelessly unsuited and totally unneeded" (p. 127). The Drucker Foundation arrived at its apocalyptic, pull-the-plug moment by observing the demographic shift in students, a change memorably captured in Marc Prensky's 2005 description of them as "digital natives" and their teachers as "digital immigrants." Prensky's categories imply a third label coveted by few educators: "digital aliens."

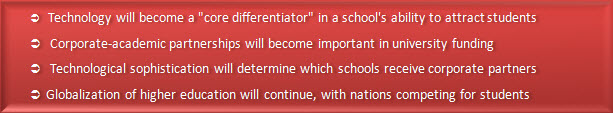

The transformation of how students learn, what we teach, and what it means to be an educated person in the 21st century is a worldwide phenomenon. A global survey (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2008) of corporate leaders and higher education executives in Europe, Asia-Pacific and the U.S. reports that digital learning technology is not only common, but:

Multimedia to the Core

If someone designs a logo for the new digital tool bag, the word "multimedia" should be emblazoned in all caps. Two decades of research have established that students across the board learn more from multimodal, multimedia lessons and feedback than from words alone. Since 1989 at least 11 major studies have confirmed this observation (Mayer, 1989; Mayer & Anderson, 1991, 1992; Mayer, Bove, Bryman, Mars & Tapangco, 1996; Mayer & Gallini, 1990; Moreno & Mayer, 1999b, 2002).

In each major study, researchers compared the test performance of students who learned from animation and narration versus narration alone; or from text and illustrations versus text alone. In all 11 studies, students who received a multimedia lesson consisting of words and pictures performed better on subsequent tests than students who received the same information in words alone.

Across the 11 studies, students who learned from words and graphics

produced 55 percent to 121 percent more correct solutions to problems

than those who learned from words alone.

Across the 11 studies, students who learned from words and graphics

produced 55 percent to 121 percent more correct solutions to problems

than those who learned from words alone. Richard Mayer was one of the first to study this remarkable difference in learning and termed it the multimedia effect, part of a set of six design principles formalized by Mayer and colleagues like Ruth Clark in research studies and instructional design manuals that help provide a scientific foundation for multimedia learning throughout corporate training units, colleges and universities.

After two decades of research in this area, the "Multimedia in the Core" program at the University of Southern California should come as no surprise. USC's innovative program is the logical next step: from students learning via multimedia to students demonstrating their learning via multimedia projects that they produce.

USC's Institute for Multimedia Literacy has designed three distinct programs to help achieve its mission of "developing educational programs and conducting research on the changing nature of literacy in a networked culture." First came the Honors in Multimedia Scholarship program in 2003 that culminates in a student producing a multimedia Honors Thesis Project in his or her major. In 2006, a Multimedia in the Core Program was launched to supplement USC's General Education courses with multimedia labs that students use to produce projects that substitute for written papers. In 2007, the Multimedia Across the College Program added upper-division courses to the mix by providing students multimedia instruction in their majors.

| Does

USC now qualify as a

one of the new "digital universities"

predicted by The Drucker Foundation and The Economist Intelligence

Unit?

Is text-based literacy being replaced by multimedia literacy at one of

America's best known universities? Would avatars,

i.e., learning

agents or pedagogical agents, be familiar to

these digital native students, who are described by one of

their IML teachers as:

" . .

. a new generation. They have skills and abilities far beyond

anything that we have ever seen before." This teacher could have added that, along with their skills and abilities, these students also bring with them a new set of expectations for learning materials. These expectations include a common element of their digital world: avatars. For |

The Gold Rush

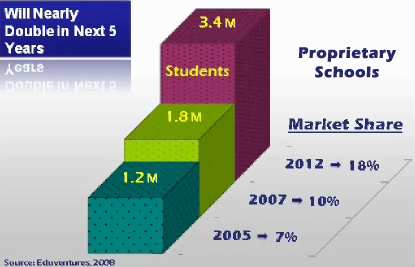

Another argument for avatars comes from what Laws (1996) calls higher education's "gold rush"--the explosion of web-based learning for adults who need and are willing to pay for pajama-clad convenience in order to earn or finish a degree while working and parenting full time.

Some

of the most

aggressive

prospectors mining this vein are for-profit education

corporations that have become synonymous with adult online

learning: Apollo Group and its flagship University of Phoenix; Career

Education Corporation with its major online schools American

InterContinental University and Colorado Technical University; ITT

Technical Training, Capella,

Kaplan, Strayer and the rest.

Some

of the most

aggressive

prospectors mining this vein are for-profit education

corporations that have become synonymous with adult online

learning: Apollo Group and its flagship University of Phoenix; Career

Education Corporation with its major online schools American

InterContinental University and Colorado Technical University; ITT

Technical Training, Capella,

Kaplan, Strayer and the rest. Data from groups like the Sloan Consortium and Eduventures are difficult to ignore and make Drucker something of a Delphic oracle to traditional education's confused Oedipus. Sloan-C's 2010 survey, Class Differences: Online Education in the United States, 2010, measured a 21 percent growth in online enrollments from the previous year, when the growth rate was 17 percent. Figures from both years far exceed the 2 percent overall growth of students in higher education and make a persuasive case that significant numbers of students are opting for online education to complement face-to-face courses or to replace them altogether.

Whether it's called a gold rush or enrollment bonanza, today there is historic pent-up demand for online education in America. In 2007, only 37 percent of this country's adults had earned an associates degree or higher, compared to 50 percent and more in Canada, Japan, France and Korea (Stokes, 2009). For this nation to stay competitive and for institutions of higher learning to stay in business, both will need to educate more adults in digital classrooms. Especially adults of color.

As Peter Stokes, executive vice president and chief research officer at Eduventures, observes: In 1980, whites accounted for 82 percent of the U.S. population. In 2020, the figure will be 63 percent, with proportional increases in the fastest growing population segments, Hispanics and African Americans, both of whom have historically lower achievement in higher education.

In addition, America's first African-American president has promised to retrain millions of workers displaced by the current economic downturn, and has put Federal dollars behind his promise. Higher education received a significant funding boost and loan reform in the Economic Stimulus Bill and 2010 budget ("The Final Stimulus Bill," 2009 & OMB, 2009).

As a dean at one large state university put it, "Either we give this new group of college students what they need, or our competition will." Her statement is a call not only for increased availability of online offerings but also for improving their quality. Good news for her and everyone else in online education: The long-awaited U.S. Department of Education's 2009 report, Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies, found that students who took all or part of their education online performed better than students in traditional face-to-face classrooms. Relevant to this discussion, another key finding was that online outcomes are enchanced by giving students more control of their learning with multimedia objects. Additional research, which we will explore below, also says that a key to significantly improving the online learning experience is multimedia materials that contain pedagogical agents.

Enter the Avatar

The Personal-Agent Effect: The DOE's 2009 finding on the importance of student-controlled multimedia learning objects provides an excellent starting point for understanding an important aspect of avatars in digital learning: the impact of personalization.

Even when the teacher-avatar is embodied only by his or her voice, the positive results have been striking. Multiple studies over the past decade have examined the effects of providing personalized audio feedback (Ice, Swan, Kupczynski, & Richardson, 2008; Oomen-Early, J., Bold, M., Wiginton, K., Gallien, T., & Anderson, N., 2008; Syncox, 2003). In Asynchronous Audio Feedback to Enhance Teaching Presence and Students' Sens

e of Community (Ice,

2007), master's and doctoral-level students who received audio

feedback showed

significant increases in comprehension and retention of material

when

compared to students who received the same feedback in written form.

Moreover, students in the study who received audio feedback

were three

times more likely to apply the content to their future work. In

addition, these students felt more involved with their education, their

peers and the school itself.

e of Community (Ice,

2007), master's and doctoral-level students who received audio

feedback showed

significant increases in comprehension and retention of material

when

compared to students who received the same feedback in written form.

Moreover, students in the study who received audio feedback

were three

times more likely to apply the content to their future work. In

addition, these students felt more involved with their education, their

peers and the school itself. When the audio is delivered by an avatar, the positive results are further enhanced. One of the most cited studies in this regard was conducted by Moreno and Mayer (2000), who asked if the use of personalized audio messages (first- and second-person language) would increase learning in multimedia lessons. In two of their experiments, groups of students were presented lessons in a personalized style by avatars ("pedagogic agents"), while other groups were presented lessons in a neutral style: audio and written text in the third person. In both experiments, the lessons containing avatars who spoke in a personalized way produced deeper learning, better problem-solving scores, and retention than did lessons that contained audio and written feedback only.

An additional study by Moreno, Mayer & Lester (2000) showed similar results. In "Life-Like Pedagogical Agents in Constructivist Multimedia Environments," the researchers sought to understand if science students who learned interactively with a life-like pedagogical agent named Herman would show deeper understanding than students who learned in a conventional environment. Although both groups demonstrated the same levels of factual recall, students taught by a life-like pedagogical agent performed better when asked to apply their knowledge in problem-solving scenarios.

To explain this result, the researchers concluded that lessons with the pedagogical agent generated in students a higher level of interest in the material and higher motivation to learn. The researchers termed this a "personal-agent effect" and attributed it to the well-documented notion that students perceive contact with learning agents as social interactions (Reeves & Nass, 1996).

The Modality Effect: An additional goal of the study was to investigate the impact of learning agents on the "modality effect"--the phenomenon that students learn better when verbal information accompanying the lesson is spoken rather than written, resulting in a reduction of cognitive load on working memory (Lee & Bowers, 1997; Mayer & Moreno, 1998; Moreno & Mayer, 1999). Once again, students who listened to audio from an avatar not only rated the lesson more favorably; these students also recalled more and were better able to use what they had learned to solve problems.

The Marketing Effect: Today it is easy to find examples of the commercial sector leveraging the ability of audio-enhanced avatars to engage us socially and to incite the multimedia and modality effects. Indeed, recent research about interactive agents from marketing studies provides additional support for the effectiveness of avatars in computer-mediated learning.

| For example, Wood,

Solomon and Englis (2005) conducted an experiment

with female

shoppers at a fictitious web site selling "personal apparel." One group

of shoppers selected their

own "shopping

assistant" (an avatar), a second group was assigned a shopping

assistant, and a third

group had none. Shoppers who were

accompanied

by an avatar participated more in the shopping, displayed greater

confidence in their buying decisions, and were overall more

satisfied with the shopping experience. The researchers hypothesized

that the avatars gave shoppers more trust in the site and more

willingness to spend their money. Multimedia authors take note: the most successful avatars in this study were the most

realistically human ones. Social Intelligence of Avatars One of the most valuable overviews of avatar use in business comes from Byron Reeves (2000) at Stanford University's Center for the Study of Language and Information. Reeves bases his analysis on the significant body of research which shows that when we engage with computer-based media, we process the experience as a social interaction. What |

Automated

Conversation Agents

All major instant messaging systems, online forum systems, and massive multi-user role-playing games include avatars today (Persson, 2003). And they're talking. The automated conversation agent, also known as a chatbot or chatterbot, uses low AI (artificial intelligence) to engage and sell us. With low AI, avatars use pattern recognition to select a pre-programmed reply to human input. Financial websites commonly use low AI chatbots to gain user trust for transactions and to reduce costs by using an avatar to automate some customer interactions. |

Although we know on a conscious level that avatars are not real humans, they nonetheless elicit from us an automatic social response. The same thing happens when we watch actors in a movie: we invoke a "willing suspension of disbelief." The result is that we process the speech, facial expressions, and body language as if they were real. Indeed, one study has found that the mere belief one is having a social interaction seems to be enough to significantly increase learning and understanding when avatar-based learning materials are used (Okita, Bailenson & Schwartz, 2007).

The more social intelligence that is present, the more socially satisfying and rewarding the media experience will be (Bailenson, Yee, Merget & Schroeder, 2006). The social intelligence of the media can determine the learner's level of attention, engagement, persistence, and subjective evaluation of the experience (Reeves, 2000).

In short, users perceive avatars as the source of the message they are viewing (Nowak & Rauh, 2005). Thus, the user's perception of the avatar significantly determines how the user receives the message. To control the message, the multimedia designer must also control how the avatar is perceived.

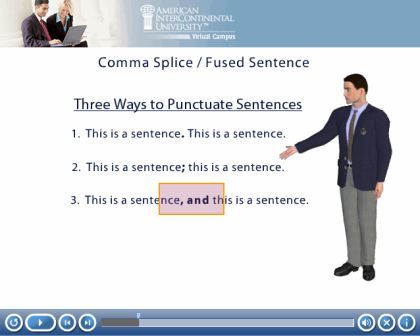

Interactivity: The research of Moreno and Mayer (1999a, 1999b, 2002) suggests that one of the most important ways to elicit a positive perception of an avatar is by increasing its interactivity: the ability to respond in real time to user feedback. This is one reason why branching scenarios are so important in learning materials. The interactivity of branching scenarios can be enhanced with the use of animated avatars

that respond to a user's input and direct the user to different parts of the lesson based upon on that input. The comma splice/fused sentence lesson above was done with Media Semantics' Character Builder program, which provides the ability to construct interactive quizzes to accompany the lessons with animated avatars. The Character Builder avatar was then imported into Adobe Captivate to create a branching-scenario lesson with animated avatar that provides feedback based upon the student's responses.

Realism: Not surprisingly, given that a key function of an avatar is to humanize the online experience, realistic avatars are preferred by most users in most circumstances. One clear demonstration of this preference can be seen on social networking sites when the user is allowed to choose a photographic avatar, illustrated avatar, or other representation of themselves. On Twitter, for example, users overwhelmingly choose photographic representations of themselves ("Are Avatars Authentic," 2009; "The Top 7 types of Twitter avatars," 2009).

Yee (2008) reports similar findings about players of online role-playing games. In a survey of over 4,000 players in MMORPGs, Yee found that players generally choose avatars that look like themselves and mirror their stereotypical gender characteristics. In addition, a Zogby survey (Reuters, 2008) of 3585 adults also found that adults in a virtual world overwhelmingly (62%) prefer an avatar that resembles themselves.

Presence & Copresence: These surveys and informal studies confirm what major research projects have found: The more anthropomorphic an avatar appears and acts, the more credible, likable and engaging it will be perceived (Nowak & Rauh, 2005). One explanation for this effect is the phenomenon of "presence"--the psychological feeling of being there. Researchers studying avatars and virtual environments often refer to the importance of "presence" (the feeling of being there) and "copresence" (the feeling of being there with someone) for the effective transfer of knowledge and skills in collaborative virtual environments.

Two factors have been identified as important in creating a sense of presence and copresence for learners in virtual environments:

First, the more multimodal a virtual environment is, the stronger the sense of presence it will generate for users (Romano & Brna, 2001; Sanchez-Vives & Slater, 2005). A pair of Israeli researchers studied one possible explanation: cognitive processing speed. In a 2006 study, "Multimodal Virtual Environments: Response Times, Attention, and Presence," test subjects learning in multimodal virtual environments were able to process sensory input faster than subjects in unimodal or bimodal lessons. The multimodal virtual environment provided subjects a richer experience in a shorter period of time, thus heightening their sense of presence (Hecht & Gad-Halevy, 2006).

Second, avatars have been shown to play an instrumental role in enhancing the user's sense of presence in a virtual environment. Numerous studies (Bailenson, Swinth, Hoyt, Persky, Dimov & Blascovich, 2005; Bailenson, Yee, Merget & Schroeder, 2006; Yee, Bailenson, & Rickertsen, 2007; Bailenson & Yee, 2006; Casanueva & Blake, 2001) illustrate the different ways that realistic, socially intelligent avatars generate a heightened sense of presence for the user in virtual learning environments. This heightened sense of presence has even been documented physiologically in one study that measured significant changes in heart rate and galvanic skin responses of test subjects to the presence, speeches and actions of avatars (Slater, et al., 2006).

As humans, our brains are wired to connect us to other humans. Social cognition theory argues that this wiring is the product of evolution and is critical to our survival: Our minds scan the environment and analyze an entity's level of anthropomorphism in order to differentiate among inanimate objects, animals, and humans, including an assessment of threat or cooperation (Kunda, 1999). As mentioned, research indicates that the more anthropomorphic an avatar is, the more the user will trust it and engage with it (Koda, 1996; Wexelblat, 1997).

In Second Life, the attempt to make avatars more realistic in their appearance and social interactions is an intense focus for those working to create body markup languages, improve natural language recognition, design independent virtual agents and other ubiquitous robots. These researchers are attempting to program the world that Neal Stephenson had only imagined been in his novel Snow Crash, which posits a virtual reality in which avatars are indistinguishable from their human counterparts.

|

Based upon the ability of

socially

intelligent

avatars to increase student

learning in digital lessons, I set out to

create a digital video version of myself that could be used in the

Second

Life tutorials I was creating and, if it succeeded, to use

this avatar in other

materials for students. My

working definition of "human

avatar" became a non-interactive video character that could be composited

into any

virtual world, web page, or multimedia lesson presented to

students. Merry Prankster: The project began as a joke. After buying an expensive camcorder, I was looking for ways to make money with it to offset my guilt. I knew of stock photo sites that bought freelancer work. What about stock video sites? In my search I downloaded one site's free sample (Stock Footage for Free) of a gorgeous beach bathed by the tropical Caribbean. Since I was also about to post a weekly video lecture for an online class, and it was the dead of winter, what fun it would be to introduce the lecture with a PIP video (picture- |

First Try, Second Life: At the time I was also making orientation videos for students who use my two properties in Second Life to fulfill class requirements, so I decided to try a chroma-keyed video in SL. This was another bedsheet production, resulting in a head-and-shoulders clip that was disappointing. It looked no different than a regular PIP and added little that wasn't in the other Second Life tutorials I had been doing, which were screen recordings with voice over and sound effects (see below). The virtual 3D world of Second Life demanded more.

Full-Frontal Avatar: Missing was a full-figured avatar that could be composited into Second Life, scaled to size, and animated to interact with the virtual environment and other avatars. Achieving those goals would require a real greenscreen and something more than trial compositing software. I settled on CompositeLab Pro due to price and ease of use. I also lucked into a 5' x 7' flexible greenscreen backdrop as part of one site's holiday specials. Another investment was a Nady wireless microphone for the camcorder. Total investment for this part of the project was around $250, but the result was encouraging--a small, life-like figure that could be easily inserted onto any digital background (see video below). Now, all I had to do was build a greenscreen studio for him to walk around in.

|

|

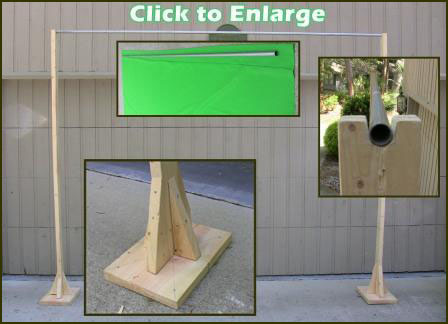

built a

rudimentary stand to hang one piece of greenscreen cloth and lay

another section on the ground. The stand is constructed of 2x4's

nailed upright to a 4x12" base

and supported with wedges screwed and

nailed into the base (click to enlarge image).

built a

rudimentary stand to hang one piece of greenscreen cloth and lay

another section on the ground. The stand is constructed of 2x4's

nailed upright to a 4x12" base

and supported with wedges screwed and

nailed into the base (click to enlarge image). At the top of each stud, a notch is rounded out to hold a crossbar from which the greenscreen cloth hangs. An open seam across the top of the cloth forms a hanger pocket that easily accommodates a half-inch wide piece of electrical conduit pipe, which comes in 10-foot lengths. I chose electrical conduit pipe for its rigidity, price, and galvanized finish. After the 11-foot panel of cloth was hung, I added one more section of cloth on the ground.

|

DIY Greenscreen Studio II: For a second production, I bought two more sections of greenscreen cloth in order to double the width of the stage to 20 feet, then a third section of cloth to drape over furniture on the stage so the avatar could sit and interact

with other objects

that would appear in the Second Life digital background video. I built

two more

stands using the same materials described above.

with other objects

that would appear in the Second Life digital background video. I built

two more

stands using the same materials described above. For this test I planned a series of seven scenes to take place in and around Escribir House, an in-world writing center. Because Escribir House has five rooms and a number of features to be shown in the video, it was necessary to storyboard the video: to draw a series of rough illustrations for each scene. Storyboarding allows pre-planning for camera angles, avatar movements, camera movements, and timing. Since two video clips from two different worlds--Second Life and the greenscreen stage--were to be composited to provide the illusion of a single world, storyboarding became essential, as did writing the script to fit the flow and timing of action.

Digital Video Workflow: Because the video's several features, it also became necessary to follow a detailed workflow. A digital workflow is a step-by-step plan for creating a specific digital product. The plan includes software, software settings, what to do in each step, and production guidelines. The term originated in photography but today also refers to outlining the creative process used in any digital medium.

| Workflow |

| 1. Shoot greenscreen segment with Canon Vixia HF100 camcorder in AVCHD (Advanced Video Codec High Definition) |

| TMPGEnc 4.0 Xpress 2. Launch TMPGEnc 4.0 Xpress. Click "Start a new project." Click "Add file" to import .MTS file (MPEG Transport System) of greenscreen clip from camera flash memory. Clip settings in TMPGEnc should be: Display mode: Progressive

3. Click Cut-Edit tab at

top of window. Use Cut-Edit to trim frames of greenscreen video clip

not to be viewed. Click OK.Aspect ratio: Aspect ratio: Display 16:9 Frame rate: 29.97 4. Click Filter tab at top of window: Use Picture Crop to eliminate areas outside greenscreen on all four sides. 5. Apply other filters as needed (color correction, noise reduction, etc.). Click OK. 6. Click Format tab at top of window. 7. Select QuickTime (.MOV) file output from list of templates on left. Click Select. 8. Under Video Codec, click on "Settings . . . " 9. Under Compression Type, choose Photo JPEG from drop down menu 10. Move slider to "Best." Click OK. 11. Click Encode tab at top of window. 12. Click "Display output preview" icon (magnifying glass) to check for "clean green" on all sides. No black can be visible on any side. If any black is visible, return to Format menu and adjust video dimensions. 13. Click "Encode" to render greenscreen video clip as a .MOV file |

| Fraps

& Second Life 14. Open Second Life and size SL viewer to 960 x 720 with Sizer tool 15. Open Fraps. Click on Movies tab. Click radio button under list of fps. Type into field: 29.97 16. Open greenscreen video clip. Minimize QT player so that it is not obscuring SL viewer. 17. Start Fraps recording in SL. 18. Start greenscreen video clip in QT. 19. Record in SL following verbal and visual cues from greenscreen video clip being played in QT. |

| TMPGEnc 4.0 Xpress 20. Import Fraps SL recording (.avi). Clip settings: Display Mode: Progressive

21. Click OKAspect Ratio" Pixel 1:1 (Square pixel) 22. Click Format tab at top of window 23. Click "Settings . . . " under Video Codec 24. For Compression Type, select Photo JPEG from drop down menu. 25. Position slider to "Best" 26. Click OK 27. Click Encode tab at top of next window. 28. Click "Display output preview" icon (magnifying glass) to check for "clean green" on all sides. No black can be visible on any side. If any black is visible, return to Format menu and adjust video dimensions 29. Click Encode to render SL screen recording as QuickTime (.MOV) |

| FXhome

CompositeLab Pro 30. Launch program and click "Select Video Clip" on startup screen 31. Import SL screen recording .MOV 32. Go to Toolbox > Media Tab > Click folder icon to "Import Media" 33. Import greenscreen video clip 34. Go to Toolbox > Media Tab > Left click on greenscreen video clip thumbnail 35. Drag greenscreen video clip thumbnail to canvas on top of SL recording 36. Go to Timeline > right click on title of greenscreen video clip 37. Select "Apply preset" from drop-down menu 38. Select "Greenscreen key" from list of presets. Click "Apply" 39. Go to Timeline > click on options arrow to expand options for greenscreen clip. 40. Select "Grade" option 41. Go to Toolbox > Info tab 42. Apply Grade options as needed (Saturation, Contrast, Sharpen, Levels, etc.) to greenscreen clip 43. Go to Timeline > click on options arrow to expand options for greenscreen clip 44. Select "Animation" option 45. Use Quad, Scale and Rotation tools to position figure 46. Click "Play" arrow 47. Trim SL screen recording for timing with greenscreen clip 48. Set In/Out frames 49. Go to main menu at top. Click on "Render" tab. Pull down to "Render" option 50. Name file and and select destination. Click Save 51. For Compression Settings, select Photo JPEG from drop down menu. Click OK to render composite project as .MOV |

| Camtasia

Studio 52. Launch program. Import composite project (size 640 x 480 Custom) and place on Timeline with other clips, if any 53. Edit final video using 640 x 480 dimensions 54. Select "Produce video as . . ." from Produce pod 55. From drop down menu, select "Custom production settings." Click Next 56. Click radio button for .MOV - QuickTime Movie. Click Next 57. Select QuickTime Options tab at top of next window 58. Under Video, click on Settings tab 59. For Compression Type, select H.264 from drop down menu 60. Position slider at "Best" quality setting 61. Click OK 62. Click on "Size" tab 63. For Dimensions, select 640 X 480. Click OK 64. Click Next four times. 65. Name file and choose destination. Click Finish to render video |

Future of the Human Avatar

Although promising work is being done in the field of artificial intelligence to make avatars more responsive to users and easier to program, the beneficial applications for educators of this exciting work seem a number of years away. In the interim, digital video compositing provides a quick, easy, cost-effective way to generate a human avatar that fits many of the characteristics of the intelligent avatar of the future.

Drawn to Life: Digital compositing can bring an online teacher to life in the digital world, a place where students are often expected to learn on their own from textual materials. The human avatar teacher can add back the personal dimension of teaching style to the built-in social

| interaction that

accompanies computer-mediated

learning. The human avatar teacher allows us to use social

interaction to increase the effectiveness of digital

lessons. The human

avatar can perform more movements, provide more expression, and present

a more

realistic appearance than current avatars and do not require

programming. What's That You Say? Since Albert Mehrabian's groundbreaking studies in the late 1960s, communication experts have been telling us about the importance of nonverbal communication (Barbour, 1976). In face-to-face communication, most studies suggest that, when it comes to communicating feelings and attitudes, 55 percent of a message's impact comes from nonverbal language and 38 percent from prosody, the suprasegmental and metaverbal elements of language such as rhythm, stress, intonation, juncture and pitch. A primary reason for complaints about the dry, boring and needlessly difficult nature of most online education is simply that text-based online instruction lacks 93 percent |

They Came, They Saw, They Learned: Student response to lessons featuring human-learning agents and avatar-learning agents is frequently the same: "It was just like being in class." And: "All teachers should be required to do this." These comments affirm that the students' interactions with these computer-mediated materials are important social interactions and, furthermore, that the effectiveness of the interaction is largely dependent upon the anthropomorphic qualities and social intelligence displayed by the avatar. The more life-like the learning agent is, the greater the student interest, perseverance, comprehension and retention.

| A New

Life: In Second Life, machinima

done with these digitally composited avatars

can play an important role in acclimating new users to the basic

components of 3D virtual reality education, introducing students to a

university's property and offerings in Second Life, and helping

students get started with specific projects or lessons. Indeed,

students

of one course who were given the option of presenting a

PowerPoint in Second Life in lieu of a written product were able

to use these machinima,

without receiving any other instruction about 3D-worlds and without ever having

visited Second Life before, to successfully present

their shows. There are multiple reasons for the success of this in-world human agent. One is the role of |

Another reason may have to do with the increased expectation for behavioral realism that comes with an increase in realistic appearance. An avatar that appears highly realistic will be perceived negatively unless it behaves as real as it looks (Slater et al., 2001; Tromp, 1998). Although avatars in Second Life can achieve a strong degree of realism in their appearance, the scripting for their actions remains rudimentary and not widely used.

Finally, research suggests that avatars which demonstrate emotional awareness, which is perceived as a significant form of social intelligence, decrease the user's personal distance and increase empathy (Selvarajah & Richards, 2005). As Garau (2005) found, the lack of such emotional expression in avatars, when compared to live video of humans, is one of the most significant barriers in collaborative virtual environments. As I tried to show in my "performance," the digital human avatar can be as expressive as a real person and thus has the ability to gain more intimacy and credibility with the user.

Summary

Research indicates that avatars will play an important role in the development of more effective digital learning materials, which can in turn improve the quality of online instruction at a time when there is economic and social pressure to do so. Avatars help to personalize the online learning experience and to increase a student's interest, attention and motivation to learn. Avatars achieve these benefits especially well when they display social intelligence, appear and act realistically, resemble the participants, and offer interaction.

A tool that educators can use to meet these criteria--digital video--is relatively inexpensive and easy to use for the nonprofessional. Moreover, this tool helps educators meet the growing demand for effective digital learning materials for expanding online populations.

At Washington State University's recent Virtual Journalism Summit, Second Life founder Philip Rosedale said that having an avatar will soon be like having an email addresses was in 1989. Back then, whether you liked it or not, Rosedale said, "you had to get an email or the world would leave you behind. Soon all of you will have to get an avatar" (draxtordespres, 2009).

Maybe that applies to our future digital lessons as well.

References

Bailenson, J. &

Beall, A. (2005). Transformed social interaction: Exploring the digital

plasticity of avatars. In R. Schroeder & A-S. Axelsson, Eds., Avatars at Work and Play:

Collaboration and Interaction in Shared Virtual Environments.,

Springer, London.

Bailenson, J., Swinth, K., Hoyt, C., Persky, S., Dimov, A., Blascovich, J. (2005). The independent and interactive effects of embodied-agent appearance and behavior on self-report, cognitive, and behavioral markers of copresence in immersive virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 14(4), 379-393. Retrieved June 1, 2009 from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/105474605774785235

Bailenson, J., Garland, P., Iyengar, S., & Yee, N. (2006). Transformed facial similarity as a political cue: A preliminary investigation. Political Psychology, 27, 373-386. Retrieved June 11, 2009 from http://pcl.stanford.edu/common/docs/research/bailenson/2005/similaritycue.pdf

Bailenson, J., Yee, N. (2006). A longitudinal study of task performance, head movements, subjective report, simulator sickness, and transformed social interaction in collaborative virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 19(1), 699-716. Retrieved June 10, 2009 from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/pres.15.6.699?journalCode=pres

Bailenson, J. Yee, N., Blascovich, J. & Guadagno, R. ( 2008). Transformed social interaction in mediated interpersonal communication. In Konijn, E., Tanis, M., Utz, S. & Linden, A. (Eds.), Mediated Interpersonal Communication (pp. 77-99). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved June 3, 2009 from http://vhil.stanford.edu/pubs/2008/bailenson-TSI-mediated.pdf

Bailenson, J., Yee, N., Merget, D. & Schroeder, R. (2006). The effect of behavioral realism and form realism on real-time avatar faces on verbal disclosure, nonverbal disclosure, emotion recognition, and copresence in dyadic interaction. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15(4), 359-372. Retrieved May 2, 2009 from ProQuest Education Journals database.

Barbour, A. & Koneya, M. (1976). Louder than words: Nonverbal communication. Merrill, Columbus, OH.

Blascovich, J. (2002). Social influence within immersive virtual environments. In R. Schroeder (ed.), The Social Life of Avatars. London: Springer-Verlag, pp. 127–145. Retrieved June 5, 2009 from The ACM Digital Library database.

Casanueva, J. & Blake, E. (2001). The effects of avatars on co-presence in a collaborative virtual environment. Technical Report CS01-02-00, Department of Computer Science, University of Cape Town, South Africa, 2001. Retrieved June 5, 2009 from http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/cache/papers/cs/

26789/http:zSzzSzwww.cs.uct.ac.zazSzResearchzSzCVCzSzPublicationszSzsaicsit01_1casanueva.pdf/casanueva01effects.pdf

Clark, K. (2009, April 2). Online education offers access and affordability . U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved May 1, 2009 from http://www.usnews.com/articles/education/online-education/2009/04/02/online-education-offers-access-and-affordability.html?PageNr=1

draxtordespres. (2009, May 1). Ethnography in Second Life: Resistance is futile! [Video file]. Video posted to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0wEWgTyHXA

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2008). The future of higher education: How technology will shape learning. Sponsored by The New Media Consortium. Retrieved April 12, 2009, from http://www.nmc.org/pdf/Future-of-Higher-Ed-(NMC).pdf

Fletcher, J.D., & Tobias, S. (2005). The multimedia principle. In R.E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 117-134). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Foreman, Joel. Avatar pedagogy. The Technology Source Archives at the University of North Carolina. Retrieved February 7, 2009 from http://technologysource.org/article/avatar_pedagogy/

Garau, M. (2005). Selective fidelity: Investigating priorities for the creation of expressive avatars. In R. Schroeder & A-S. Axelsson, Eds., Avatars at Work and Play: Collaboration and Interaction in Shared Virtual Environments., Springer, London.

Hecht, D. & Gad-Halevy. (2006). Multimodal virtual environments: Response times, attention, and presence. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15(5), 515-523. Retrieved June 9, 2009 from Academic Search Premier database.

Hesselbein, F., Goldsmith, M. & Beckhard, R. (1997). The organization of the future. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P., & Wells, J. (2007). Asynchronous audio feedback to enhance teaching presence and students' sense of community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(2), pp. 3-25. Retrieved from http://www.adobe.com/education/resources/hed/articles/pdfs/v11n2_ice.pdf

Ice, P., Swan, K., Kupczynski, L., & Richardson, J. (2008). The impact of asynchronous audio feedback on teaching and social presence: A survey of current research. Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications. Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Reader.NoAccess&paper_id=29162&CFID=8862842&CFTOKEN=17400862

Johnson, L., Smith, R., Smythe, J. & Varon, R. (2009). Challenge-Based learning: An approach for our time. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Lee, A.Y. & Bowers, A. N. (1997). The effect of multimedia components on learning. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 340-344. Reprint.

Karp, D. (2009). "Are avatars authentic or effective?" Retrieved April 30, 2009 from http://www.limeduck.com/2009/03/04/are-avatars-authentic-or-effective/

Kluge, S. & Riley, L. (2008). Teaching in virtual worlds: Opportunities and challenges. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 5, 127-135. Retrieved February 23, 2009 from http://proceedings.informingscience.org/InSITE2008/IISITv5p127-135Kluge459.pdf

Koda, T. (1996). Agents with faces: The effects of personification. Proceedings of HCI 1996. London.

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Laws, B. (1996). Distance learning's explosion on the internet. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 7(2), 48-64. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. EJ523018) Retrieved May April 4, 2009, from ERIC database.

Mayer, R. (1989). Systematic thinking fostered by illustrations in scientific text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 240-246.

Mayer, R. & Anderson R. (1991). Animations need narrations. An experimental test of dual-processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312-320.

Mayer, R. & Anderson R. (1992). The instructive animation: Helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 444-452.

Mayer, R., Bove, W., Bryman, A., Mars, R., & Tapangco, L. (1996). When less is more: Meaningful learning from visual and verbal summaries of science textbook lessons. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 64-73.

Mayer, R. & Gallini, J. (1990). When is an illustration worth ten thousand words? Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 64-73.

Mayer, R. & Moreno, R. (1998). The split-attention effect in multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312-320.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (1999a). Multimedia-supported metaphors for meaning making in mathematics. Cognition and Instruction, 17, 215-248.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (1999b). Cognitive principles in multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity effects. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 1-11.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (2002). Engaging students in active learning: The case for personalized multimedia messages. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 724-733.

Nagao, K. & Takeuchi, A. (1994). Social interaction: Multimodal conversation with social agents. Proceedings of the Eleventh National Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://www.aaai.org/Library/AAAI/aaai94contents.php

Nowak, K. & Rauh, C. (2005). The influence of the avatar on online perceptions of anthropomorphism, androgyny, credibility, homophily, and attraction. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1). Retrieved May 10, 2009 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/nowak.html

Office of Management and Budget. (2009). President Obama's fiscal 2010 budget. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/fy2010_key_college/

Okita, S., Bailenson, J., Schwartz, D. L. (2007). The mere belief of social interaction improves learning. In Proceedings of the Twenty-ninth Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. August, Nashville, USA. Retrieved June 11, 2009 from The ACM Digital Library database.

Oomen-Early, J., Bold, M., Wiginton, K., Gallien, T., & Anderson, N. (2008). Using asynchronous audio communication (AAC) in the online classroom: A comparative study. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 4, 267-276.

Prensky, M. (2005). Listen to the natives. Educational Leadership, 63(4), 8-13. Retrieved April 12, 2009 from http://www.ascd.org/authors/ed_lead/el200512_prensky.html

Reeves, B. (2000). The benefits of interactive online characters. Retrieved April 18, 2009 from http://www.sitepal.com/pdf/casestudy/Stanford_University_avatar_case_study.pdf

Reeves, B. & Nass, C. (1996). The media equation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Reuters, E. (2008). Poll: Most adults don't want fantasy avatars. Second Life News Center. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://secondlife.reuters.com/stories/2008/01/31/poll-most-adults-dont-want-fantasy-avatars/

Romano, D. & Brna, P. (2001). Presence and reflection in training: Support for learning to improve quality decision-making skills under time limitations. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 4(2), 265-278. Retrieved May 11, 2009 from Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection database.

Sanchez-Vives, M. & Slater, M. (2005). From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 6, 332–339. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from Academic Search Premier database.

Selvarajah, K. & Richards, D. (2005). The use of emotions to create believable agents in a virtual environment. International Conference on Autonomous Agents: Proceedings of the fourth international joint conference on Autonomous agents and multiagent systems, July 25-29, 2005. Utrech University, The Netherlands. Retrieved, May 12, 2009 from The ACM Digital Library database.

Shanteau, J. & Nagy, G. (1979). Probability of acceptance in dating choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 522-533.

Slater, M., Guger, C., Edlinger, G., Leeb, R., Pfurtscheller, G., Antley, A., et al. (2006, October). Analysis of physiological responses to a social situation in an immersive virtual environment. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 15(5), 553-569. Retrieved June 13, 2009, from Computers & Applied Sciences Complete database.

Slater, M. & Steed, A. (2001). Meeting people virtually: Experiments in virtual environments. In R. Schroeder, Ed., The Social Life of Avatars: Presence and Interaction in Shared Virtual Environments, Springer Verlag, Berlin, 2001.

Sloan-C. (2008). Staying the course: Online education in the United States, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/survey/staying_course

Stoilescu, D. (2008). Modalities of using learning objects for intelligent agents in learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects. Retrieved May 1, 2009 from http://ijklo.org/Volume4/IJELLOv4p049-064Stoilescu394.pdf

Stokes, P. (2009). From survival to sustainability. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved May 1, 2009, from http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2009/04/17/stokes

Syncox, D. (2003). The effects of audio-taped feedback on ESL graduate student writing. (Master's thesis). Available at http://digitool.library.mcgill.ca/webclient/StreamGate?folder_id=0&dvs=1301848649805~480

The final stimulus bill (2009). Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/02/13/stimulus

The New Media Consortium. (2005). A global imperative: The report of the 21st Century literacy summit. Retrieved February 8, 2007, from http://www.adobe.com/education/solutions/pdfs/globalimperative.pdf

The top 7 types of Twitter avatars. (2009). 10,000 Words. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from http://www.10000words.net/2009/05/top-7-types-of-twitter-avatars.html

Tromp, J., Bullock, A., Steed, A., Sadagic, A., Slater, M., & Frecon, E. (1998). Small group behaviour experiments in the COVEN Project. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 18(6), 53-63.

Vander Valk, F. (2008, June). Identity, power, and representation in virtual environments. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 4(2). Retrieved January 30, 2009 from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol4no2/vandervalk0608.htm

Wexelblat, A. (1998). Don't make that face: A report on anthropomorphizing an interface. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from

http://www.aaai.org/Papers/Symposia/Spring/1998/SS-98-02/SS98-02-028.pdf

Wood, N. , Solomon, M., & Englis, B. (2005). Personalization of online avatars: Is the messenger as important as the message? International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, 2(1/2), 143-161.

Yee, N. (2008). Our virtual bodies, ourselves? In The Daedalus Project: The Psychology of MMORPGS by Nick Yee. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://www.nickyee.com/daedalus/archives/001613.php?page=1

Yee,

N., Bailenson, J. & Rickertsen, K. (2007). A

meta-analysis of the impact of the inclusion and realism of human-like

faces on user experiences in interfaces. Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, April 28-May 03,

2007, San Jose, California. Retrieved June 2, 2009 from The ACM Digital

Library database.

Zajonc, R., Adelmann, P., Murphy, S. & Niendenthal, P. (1987). Convergence in the physical appearance of spouses. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 335–346.

Zajonc, R., Adelmann, P., Murphy, S. & Niendenthal, P. (1987). Convergence in the physical appearance of spouses. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 335–346.

copyright 2011

© David Taylor

david@peakwriting.com

Second Life: David Hecht

david@peakwriting.com

Second Life: David Hecht